Alfredo Luís da Costa Contents Biography Notes References Navigation menuO Atentado de 1 de Fevereiro de 1908 (Regicídio)- Na versão de Aquilino RibeiroA História na obra de Pedro da Silveira por José Guilherme Reis Leite"O Atentado de 1 Fevereiro de 1908 (Regicído) na versão de Aquilino Ribeiro""Manuel Buíça e Alfredo Costa: mártires injustiçados"

1883 births1908 deathsPeople from Castro VerdePortuguese republicansPortuguese journalistsPortuguese FreemasonsPortuguese assassinsRegicidesAssassins of heads of governmentDeaths by firearm in Portugal

PortugueseCarbonáriaMasonManuel BuíçaCarlos I of PortugalPrince Royal, Luis FilipeLisbon RegicideCasévelCastro VerdeAlentejoLisbonAngra do HeroísmoEstremozAquilino RibeiromasonAquilino RibeiroLuz de AlmeidaMachado SantosLisbonMunicipal Library Elevator CoupManuel BuiçaPalace of NecessidadesPortuguese Republicancoup d'etatCarbonáriamasonryJoão FrancoManuel BuíçaMachado SantosBrowningManuel BuíçaOlivaisJoão FrancoTerreiro do PaçoD. JosékioskcelllandauQueenPrince RoyalhumerusmorguethoraxManuel BuíçaSão JoãoFerreira do AmaralréisEstado NovoproclamationFirst Portuguese RepublicAfonso Costa

Alfredo Costa | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Alfredo Luís da Costa 24 November 1883 Casével, Castro Verde |

| Died | 1 February 1908(1908-02-01) (aged 24) Lisbon |

| Cause of death | Shot by police |

| Occupation |

|

| Parent(s) |

|

| Details | |

| Date | 1 February 1908 |

| Location(s) | Terreiro do Paço |

| Target(s) |

|

| Killed | 2 |

| Injured | 1 |

| Weapons | Browning revolver |

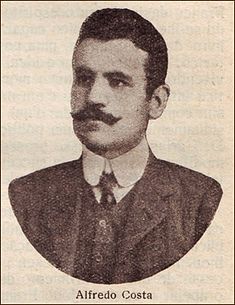

Alfredo Luís da Costa (24 November 1883 – 1 February 1908), was a Portuguese publicist, editor, journalist, shop assistant and salesman who was part of the Portuguese Carbonária and a Mason, best remembered for being one of the two assassins (with Manuel Buíça) credited in the assassination of King Carlos I of Portugal and the Prince Royal, Luis Filipe, during the events that became known as the 1908 Lisbon Regicide (on 1 February 1908), ultimately leading to his death.

Contents

1 Biography

1.1 Elevator coup

1.2 Assassination to death

1.3 Autopsy and burial

1.4 Afterward

2 Notes

3 References

Biography

He was born to Manuel Luís da Costa and Maria João da Costa in the small village of Casével, Castro Verde.

From a small farm in the Alentejo, he travelled to Lisbon where he worked for his uncle, a member of the Associação dos Empregados do Comércio de Lisboa (English: Association of Commerce Workers of Lisbon), and learned the alphabet in his shop.

On meeting Alfredo Luís, Raul Pires described him as "...of a serious physiognomy, almost tragic" and with "big brown eyes, slow-moving, with a stance that appeared sleep-walking...with a moustache on his face, the nose lightly bent to the left. It is probable that he had untreated tubercolosis...and a perceptible bend in his back..."[1] Later, Costa would continue as a sales clerk, after leaving the employ of his uncle, and traveling the country. Self-trained and a natural rebel, in Angra do Heroísmo he worked for a labour newspaper for workers in commerce, where as an able journalist he continued to submit weekly dispatches. While in Angra, he was also the driving force behind the Núcleo da Juventude Anarco-Sindicalista (English: Center for Anarchist-Syndicalist Youth)[2] He continued his career in 1903, in Estremoz, where he was a republican propagandist, contributing to local newspapers with an unlimited dedication. With a small loan from a colleague he founded a small bookstore, A Social Editora, with Aquilino Ribeiro, where he edited several pamphlets against the regime, and distributed them door-to-door. This included his A Filha do Jardineiro (English: The Gardener's Daughter) an ironic romance that disparaged the royal family over seven decades, and which consumed most of his savings.

A republican radical, though not an extremist, he was a mason in the Lisbon Mountain Lodge with contemporaries such as Aquilino Ribeiro, Luz de Almeida and Machado Santos.

By 31 January 1908 he lived in the second-floor apartment at Rua dos Douradores, 20 in Lisbon. Costa was single, childless, an employee in commercial business, while collaborator in several publications and administrator of the weekly O Caixeiro.

Elevator coup

On the disastrous evening of the Municipal Library Elevator Coup (28 January 1908)[3] Costa lead a group of 20 men (with Manuel Buiça) to assault the Royal Palace of Necessidades, but modified their strategy and, instead, attacked the Quartel dos Lóios. Later they confronted several members of the Guarda Municipal (English: Municipal Guard) near Rua de Santa Bárbara when they were waiting for a mortar explosion to signal the main attack. Planned, financed and armed by elements of the Portuguese Republican and Progressive Dissidency Parties, the coup d'etat was to be carried out by members of the Carbonária, Formiga Branca and masonry in order to proclaim a Republic and/or assassinate Prime Minister João Franco.

The coup failed when the police were tipped-off to the conspiracy and had reinforced strategic posts throughout the city. As several members of the Republican registry were rounded-up, Alfredo Costa was able to escape the police sweep, as he was not at his pre-designated post for the coup. In fact, the prisons were full of high-ranking members of the conspiracy who were easily picked up as they meandered through the city.

In the backroom of the Café Gelo, a popular and frequented destination of the Carbonária and republicans was relatively empty. With a small group, that included Manuel Buíça, Alfredo Costa continued to gather in the cafe, even as others silently or quickly passed by without entering. Actually, Costa continued to freely walk through the city, congregating with republican elements, while exhorting his peers to continue the struggle. During an encounter with Machado Santos and Soares Andrea at the Café Gelo, shortly after the attempted coupe, he affirmed:

"If someone attempts to grab me...I will burn him to pieces"[1]

This refrain was followed by a conspicuous patting of his coat, where he carried his Browning revolver.

Assassination to death

Alfredo Costa on the date of his death, after the assassination of King Carlos I and the Prince Royal, 2 February 1908

On the morning of February 1908, Alfredo Costa met with Manuel Buíça and other Carbonárias in the Quinta do Xexé, in Olivais, where they finalized the assassination of João Franco and members of the Royal Family.[4] It is unclear when the decision was made to kill the King, but it was part of the instructions given to the cell that Alfredo Costa and Manuel Buíça belonged to, during the Elevator coup attempt.[5]

At about two in the afternoon, Manuel Buíça and three others had lunch in a corner-table near the kitchen in the Café Gelo. The assassins talked quietly, as Alfredo Costa quickly ate his meal. Manuel Buíça was the first to get up, and he advised his cohorts that he would go catch "the boat" (referring to his intent to meet the King's ferry as it arrived). By four o'clock, Alfredo Costa, Fabrício de Lemos and Ximenes, assumed positions under the arcade of the Minister of the Kingdom in the Terreiro do Paço. Manuel Buíça with Domingos Ribeiro and José Maria Nunes, positioned themselves within the square, near the statue of D. José across from the Ministry, alongside a tree and kiosk. The six-man cell await along the planned route of the Royal Family, along with the rest of the gathered population, eyeing the arrival of the boat on which they travelled.

After the disembarking, around 05:20, Manuel Buíça had begun firing on the landau. Alfredo Costa jumped on the carriage and fired two shots into the already lifeless body of the monarch: Buíça had already killed the King with his first shot. The Queen confronted Costa with her bouquet of flowers, yelling: "Infames! Infames!" (English: Infamous). Costa turned to the Prince Royal and fired a shot that hit him in the chest, but being of a small calibre it did not penetrate the sternum, and the Prince opened fire on Costa, firing four rapid shots with his service revolver. Costa fell from the carriage; later, in the autopsy, it was learned that the shots fractured Costa's left humerus and although it was not fatal, it impeded him from holding onto the edge of the landau. A mounted cavalry officer, Lieutenant Figueira, then attacked Costa with his sabre, wounding him in the back and face. The municipal police then committed to the attack, and two agents apprehended him and dragged the assassin to the police quadrant near the city hall. At the entrance he was shot by an unidentified officer or member of the Municipal Guard, which perforated his lung, killing him.[6]

Autopsy and burial

Mourners at the graves of Alfredo Costa and Manuel Buiça, around August 1908

Alfredo Costa was buried on 11 February 1908. The day before, a group of three men, members of the Associação do Registo Civil[7] (English: Civil Registry Association) who appeared outside the morgue to convince the director to provide a civil funeral.

Autopsied in the early evening of the same day, the coroner found a total of 11 wounds throughout his body. There were three wounds in his head, two on the back and one in the chest which were caused by a sword, but were not considered fatal. A seventh wound corresponded to a wound on the left side of his face. The rest of the wounds were caused by gunshots: one in the lower back, one straight through wound in the armpit and the humerus wound (both attributed to Prince Luís Filipe) and finally, a wound caused by a bullet that hit him in the upper part of his chest and perforated his lung, crossed his thorax, fracturing and lodging itself in a rib. This last wound was fatal, and responsible for Costa's death.[8] The projectile was not recovered, but from the description, was a small 5–10 mm bullet from a 6.35–7.65 calibre automatic, which was not in standard for the Portuguese police at that time. This reinforced a theory that was promulgated by conspiracy theorists: that Alfredo Costa was killed by people who did not wish the assassins to be interrogated.[9]

Afterward

Costa's body, along with that of Manuel Buíça and João Sabino (an unfortunate victim of the chaos) were prepared and delivered (except for Sabino's body) to the cemetery of Alto de São João. Arriving, the coffins were sealed and buried (in markers 6044 e 6045); in 1914 the bones of the assassins were transferred to the mausoleum chamber 4251.

Ironically, the acclamation government of Ferreira do Amaral permitted public mourning by republicans, who had apologized for the assassinations and who considered the assassins friends of the Fatherland. Approximately 22,000 people would pay their respects at the graves of Costa and Buíça; the civil ceremony was organized by the Civil Registry Association, which furnished the flowers and paid 500 réis per person and 200 réis per child that appeared at the graves.[10] After the establishment of the Republic, the same Association acquired land in the cemetery in order to construct a monument to the heroic liberators of the Fatherland (as written on the request to the Lisbon city hall authorities in their petition). The monument was eventually dismantled by the Estado Novo government and the bodies transferred to other locations within the cemetery, and the monument's elements were abandoned.

The final report into the assassination of King Carlos and Prince Royal, which was ready for judicial investigation disappeared (on 25 October 1910), shortly after the proclamation of the First Portuguese Republic. Judge Almeida e Azevedo submitted the process to Dr. José Barbosa, member of the Provisional Government, who was responsible for delivering it to Afonso Costa, the new Minister of Justice.

Notes

^ ab O Atentado de 1 de Fevereiro de 1908 (Regicídio)- Na versão de Aquilino Ribeiro

^ A História na obra de Pedro da Silveira por José Guilherme Reis Leite

^ The Library Elevator, which was dismantled in 1920, connected the Praça do Município (then called the Largo do Pelourinho) with the Largo da Biblioteca in Lisbon, and was the site of the arrest of various revolutionaries involved in the attempted coupe that was then referred to as the Janeirada, but was popularly referred to as the Municipal Library Elevator Coup

^ From the story recounted by Fabrício de Lemos, one of the conspirators, later written down by António de Albuquerque in A execução do Rei Carlos (English: The Execution of King Carlos); although with all probability the plans to kill the monarch had been completed, the team had met to adjust the details between the members, owing to the previous days detentions at the Municipal Library Elevator.

^ Jorge Morais, 2007, pp. 123–126

^ Mendo Castro Henriques, p. 235

^ The Association was created by Portuguese Masons and Republicans to facilitate the organization and development of a new Portuguese civil code as a prelude to the formation of a Republic. Formed in 1895, its precepts were institutionalized in the establishment of the Civil Registry Code and the transfer of documents from Church to governmental institutions, in the Lei da Separação da Igreja do Estado (English: The Law on the Separation of Church and State).

^ Mendo Castro Henriques, 2008, pp. 242–243

^ Mendo Castro Henriques, 2008, p. 244

^ Marquesa de Rio Maior, 1930

References

Ventura, António (2008). A Carbonária em Portugal 1897–1910 [The Carbonária in Portugal (1897–1910)] (2nd ed.). Livros Horizonte. ISBN 978-972-24-1587-3..mw-parser-output cite.citationfont-style:inherit.mw-parser-output .citation qquotes:"""""""'""'".mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registrationcolor:#555.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration spanborder-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output code.cs1-codecolor:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-errordisplay:none;font-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-errorfont-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-maintdisplay:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-formatfont-size:95%.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-leftpadding-left:0.2em.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-rightpadding-right:0.2em

Ribeiro, Aquilino (2008). "O Atentado de 1 Fevereiro de 1908 (Regicído) na versão de Aquilino Ribeiro" [The Attempt on 1 February 1908 (Regicide)] (PDF). Republica e Laicidade Associação Cívica. Retrieved 23 July 2010.

Morais, Jorge (2007). Regicídio – A Contagem Decrescente [Regicide: The Untold Story] (in Portuguese). Lisbon, Portugal: Zéfiro. ISBN 978-972-8958-40-4.

Pinto, José Manuel de Castro (2007). D. Carlos (1863–1908) A Vida e o Assassinato de um Rei [D. Carlos (1863–1908): The Life and the Assassination of the King] (in Portuguese). Lisbon, Portugal: Plátano Editora. ISBN 978-972-770-563-4.

Castro Henriques, Mendo (2008). Dossier Regicídio o – Processo Desaparecido [The Regicide Dossier: The Missing Process] (in Portuguese). Lisbon, Portugal: Tribuna da História – Edição de Livros e Revistas, Lda. ISBN 978-972-8799-78-6.

Esperança, Carlos (December 2007). "Manuel Buíça e Alfredo Costa: mártires injustiçados" [Manuel Buíça e Alfredo Costa: unjustified martyers] (in Portuguese). Coimbra, Portugal: República Laicaide associação cívica. Retrieved 19 August 2010.